Extremely Obvious Thoughts I Had in Late November 2024

Here are some extremely obvious ideas I wrote short notes on in the last few weeks.

1. Happiness is Good Actually

I recently learned about antifrustrationism, a form of negative utilitarianism maintaining that you can’t do better (morally) than a world with fully satisfied preferences. Apparently Peter Singer once defended this concept:

The creation of preferences which we then satisfy gains us nothing. We can think of the creation of the unsatisfied preferences as putting a debit in the moral ledger which satisfying them merely cancels out.

I think this idea is very clearly wrong for three reasons.

First, once a preference exists, you can do much better than merely satisfying it. Human beings evolved a preference for sugary and fatty foods, which could be (temporarily) satisfied by eating berries or nuts or whatever in the ancestral environment. But in the modern environment, all sorts of superstimuli allow me to satisfy this preference at 500% the strength of anything my innate preferences ever adapted for, which explains why I feel way better than neutral any time I drink a cream soda.

Second, I disagree that preferences are the right way to think about utility. Among other problems with the preference view, the word suggests our utility functions are either satisfied (which sounds neutral) or unsatisfied (which sounds bad). But on a hedonic view, one instead views preferences as sliding scales along which moving up feels good and moving down feels bad. I think this view better accounts for many aspects of our painful and pleasurable experiences, for instance (a) our preferences seem subjectively to have ‘set points’ which it feels good to be above and bad to be below (e.g., some amount of social inclusion feels adequate, while less feels lonely and more feels great), and (b) the impact of preferences on utility seems to have more to do with the direction one is moving along the sliding scale for that preference (e.g., eating is a pleasurable experience even if you’re currently hungry) than with their current location on that scale.

The hedonic view also does a much better job accounting for the fact that things can give us utility despite us not having a preference for them: for instance, I can derive pleasure from a food I’ve never eaten before and didn’t know I wanted. I think the antifrustrationist view would have a hard time explaining this phenomenon.

Third, I think antifrustrationism implicitly assumes some kind of moral realism that I don’t believe exists. Sure, you can draw the line for “the point where I stop thinking human existence is bad and start thinking it’s good” way the hell up at the top of the scale where people are filled with nothing but euphoric bliss every second of every day, and there’s no objective standard I can point to to prove that someone who feels happiness at a level ever-so-slightly below that threshold for one second before going back to their utopian mental state doesn’t have a net-negative life. But the relevant question seems to be whether it is psychologically true that one sees preference satisfaction as morally neutral rather than morally good. To me the answer is absurdly easy; when people I love make me laugh so hard I cry, I find it extremely obvious that I place positive moral value on having at least some kinds of experiences in the universe.

2. Pain is Bad Actually

Supposedly pain asymbolia is a condition that causes people not to experience pain as unpleasant and which exists.

I feel super confused by this claim and feel somewhat confident that it is impossible for such a condition to exist. I think pain asymbolia must actually be one of two conditions: either one where (a) the signal that my brain interprets as pain is interpreted as a qualitatively different physical sensation (e.g. tingling), or where (b) important parts of the brain which respond to pain in normal people don’t interact with pain signals in the same way, such that pain asymbolics actually do experience pain in the same way but for whatever reason their reflexes, verbal cortex, etc. don’t know it. I think this because I don’t know what on earth “pain” could possibly mean if not “the experience of unpleasantness.”

The condition seems like it needs a better name; I think we should gatekeep the word “pain” for those of us for whom suffering sucks.

3. Anachronisms Still Disprove The Book of Mormon

There are a lot of anachronisms in the Book of Mormon, like horses, swords, and wheels. These things weren’t present in ancient America, so I think this pretty much settles the debate about the Book of Mormon’s historical accuracy. But a recent Mormon defense doc that’s been gaining a bit of traction claims that actually, looking at alleged anachronisms in the Book of Mormon over time is evidence for its historical accuracy, because critics used to suspect there were 205 anachronisms in the Book of Mormon but a lot of those things have actually been found in ancient America since then and now there’s only 38 anachronisms.

The writer asks, “Isn’t it logical that if Joseph Smith made up the Book of Mormon, it would prove more ludicrous over time? Yet the opposite has happened.”

I think the answer is no, and the reason feels kind of interesting to me! People used to know hardly anything about ancient America, so yeah, pretty much everything looked like a potential anachronism at one point. As we learned more about ancient America, some of those uncertainties were resolved in favor of team Mormonism, and some weren’t. Critics undoubtedly knew that this would happen. The problem is that for the Book of Mormon to be historically accurate, it needs to win not just some of these anachronisms, but all of them.

In other words, it’s not evidence for your claim that you look less wrong now than you used to. You’re supposed to look right.

(Side note, I also think the evidence “disproving” 167 of the original 205 suspected anachronisms is in many places quite weak - e.g., the “found” anachronisms are often nowhere near their alleged historical location in the Book of Mormon).

4. The Talking Stage is a Prisoner’s Dilemma

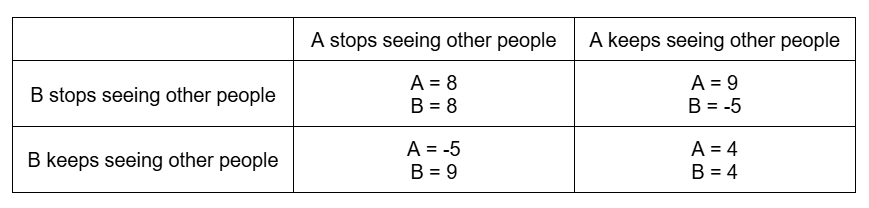

I hadn’t considered this before but you can kinda view the process of romantic courtship as an iterated prisoner’s dilemma. Consider the case of two people in the early stages of dating who would both be thrilled if the other person started dating them exclusively, but who each have a slight preference to keep their own options open. Their reward functions might look like this:

Per the defining feature of a prisoner’s dilemma, the Nash equilibrium of this game is for both people to continue seeing other people. In other words, even if two people would be twice as happy to commit to each other as they would be to continue dating casually, their small mutual incentives to retain their backup options might lead them each to remain in a perpetual hoe phase. That is too bad.

5. Berkeley Haas is Not Waste Free

The building I work in on Berkeley’s campus doesn’t have any trash cans (only recycling and compost bins) and prides itself on being “waste free.”

It’s not waste free. There are vending machines in the building where you can buy products in disposable packaging. People are just forced to carry their trash around all day and throw it away somewhere else later.

6. Talk to People You Like at Parties

In the last year I’ve noticed that some parties have shifted from feeling like a fun time to feeling like a stodgy networking event. I think this is a combination of four things: (1) as I’m accruing distance from college, I’m finding myself getting invited to parties with increasingly older crowds, and I think I might relate to people substantially older than me in a pretty formal way by default, (2) meeting people at parties doesn’t feel as exciting to me currently as it used to because my demand for new friends is lower, and (3) my social circles generally do a bad job separating personal and professional relationships, but also, I’m pretty sure at least some of it is:

(4) There feels like a weird stigma against talking to people you already know well - or people you could hypothetically get to know well outside of the party - at parties.

I think that if you also feel this way, it’s maybe good to consider that life is short and highly compatible friendships are super hard to find. And you are not in fact going to talk to that coworker/housemate/person in your class outside of this party, I guarantee you’ll both be very busy next week and also the week after that. Consider also, the median conversation at a house party kind of sucks; it’s probably between you and some guy who mostly wants to talk about how masculinity is in crisis, or who only asks you boring questions about things like where you’re studying and where you’re from, or some guy who won’t shut up about his halfway-underwater-already startup.

I have a strong suspicion that if people actually optimized their behavior at parties for their own personal enjoyment, then everyone besides 90th-percentile+ extroverts would talk mostly to their pre-existing friends and only sometimes to strangers rather than mostly to strangers. I’m probably projecting, but imagine how nice that would be! But a lot of people seem to feel guilty doing this for some reason? Instead no, you must now endure a small talk with this uninteresting guy for fifteen minutes.

All this is to say, I recently got kind of scolded by someone semi-close to me for talking with them rather than meeting new people I’d never met before at a party. I was like, “oh sorry, I didn’t mean to monopolize your time,” and they were like, “oh no, I already know most people here, I just meant that you should talk to whoever you don’t know here.” I wanted to be like, uh, in that case, I can make my own grown up decisions about which conversations will bring me more or less utility. (Of course, if you’re annoying someone, that’s a different thing, you should obviously be attentive to your conversational partner’s engagement and anyone is welcome to exit any conversation at any time - I’m just saying nobody should feel compelled by arbitrary norms to not have as much fun as they could be having at these things.)

We don’t have to do parties this way. You don’t even have to go to parties to begin with. Given that you are going to any particular party, I think you should feel free to pick and choose only the interactions that will make the party worth your attendance and not feel any weird guilt over not having a less enjoyable time.